History and Development of

REN YI WU KWAN TANG SOU DAO

By Grandmaster M K Loke

The history of humankind shows a development of ideas and principles – from the first Chinese abacus (counting machine) to the present day digital supercomputer; from the Chinese war rocket to the space shuttle. There is no area of human interest that has not shown this growth and development. All that is needed for this to continue apace is a long history upon which old ideas and principles (“traditions”) are built upon and continue to be built upon.

The countries of the Far East venerate the Old Ways, the traditions, to a greater extent than is found in the West. These traditions have grown through the long years and each successive generation has added clearer insights, deeper understanding and greater sophistication to what has gone before. That which stands still does not renew itself with new ideas, and that which does not renew itself dies.

China has a very old civilisation and deep rooted traditions. During its time, it has fought many, many battles – both within and outside its borders – so it is hardly surprising that efficient principles of warfare have developed. Though weapons have changed, the principles are as valid today as they were when they were originated. Take for example, The Art of War by that great Chinese warrior-philosopher, Sun Tzu. The advice given in that manual is as relevant today as when it was written, approximately two thousand years ago. Many western corporate managers use the work as a reference on how to succeed in the “wars” of the business world.

China was the first and the original Far Eastern centre of civilisation and imperial superpower. Korea was no more than a semi-autonomous province of China, paying its tribute and being left alone largely because it was of no interest to the Chinese nation. Japan, an island community, lies at the periphery of imperial China. It traded with China and trod warily in the shadow of its giant neighbour until the end of the nineteenth century when China’s decay had robbed it of all power. The written language of both Korea and Japan is Chinese, though both nations have subsequently developed their own scripts. Even so, the classic written text of these two nations are still in Chinese today.

In a country as vast as China and with its long history, it is unsurprising that many military geniuses have emerged. With China’s veneration for tradition, their genius has been both preserved for future generations and built upon as changing circumstances brought about development into new areas. But this same veneration recognises the value of the principles that have been identified at such great cost.

Accordingly, they have never been disclosed to just anyone! What is the point in having valuable knowledge that will help one protect one’s country, only to give that knowledge away to neighbouring states, some of which offer only a dubious and short-term friendship? This wisdom meant that the Chinese military principles and techniques were not taught to people outside of their fighting force, the family and their own race. Even today the better traditional Chinese masters will not teach non-Chinese and those who do, insist on a long probationary period before students are admitted as disciples. The Chinese call this privileged status bai shi, loosely meaning ” worship teacher” and it is conferred through an ancient ritual during which the student kneels before the master and pledges loyalty/secrecy. Once the master accepts the student, the latter is said to be an “inside door” disciple.

This is not to say that the Chinese will not teach martial principles and techniques to outside door students and even foreigners, though the value of what is given away is very limited. Thus it was that in CE1393, thirty-six Chinese families came to live in the Okinawan village of Toci (also known as Kume Mura) as part of a token military and political presence. From time to time, military attaches would teach rudimentary martial techniques to Okinawans, perhaps with the intention of encouraging unrest between the islanders and the occupying mainland Japanese forces. The Okinawans appreciated Chinese instruction and in recognition of it, one of the names they gave to their developing art was T’ang Hand (To Te in Okinawan).This name comes from the T’ang period of China which extended from CE618-907, and during this period a high level of martial art was practised. The Tang period is known as China’s “Golden Age.” The Chinese today still refer to themselves as “Tang” people.

At this point, I wish to pause to mention the Shaolin Temple. Ch’an (Zen) Buddhism was introduced to China by an Indian warrior monk named Bodidharma (Da Mo is the Chinese reading of his name). One of the places he stayed at was the monastery of Shaolin and it is claimed that whilst there, he taught the monks two sets of exercises to toughen them up so they could meditate for longer periods. Some people claim that these two sets of exercises formed the basis of Chinese martial art but this, of course, could not be true. Chinese martial arts predate Bodidharma’s visit to Shaolin circa CE600 and there is no evidence to link the exercises he taught with actual martial art practice.

China had no national police force and isolated communities of monks were responsible for their own safety. Being Buddhists, the monks were not allowed to use bladed weapons so they became proficient with the quarterstaff, the stick, their bare hands and feet. During the T’ang period in particular, some monasteries became well known for the martial skill of their monks and of these, Shaolin is particularly celebrated. The monastery received several royal commendations for the valour of its monks though eventually, this was to prove its undoing.

Korea, like Okinawa, also formed a buffer zone between Mainland China and warlike Japan, so the same pattern was repeated there. Admiration of Chinese military tradition was never more evident than in the 16th century, when Admiral Yi adopted an entire Ming dynasty military training manual (the Wu Yi Tu Pu Tong Tse) for Korean use This Chinese manual covers an extensive array of military weapons used in those days, including a chapter on empty-hand fighting, labelled as “fist method” Chuen Fa (reads as kwon bup in korean). The Koreans valued this manual very highly even today and called it the Moo Yei Do Bo Tong Ji. However, it is important to realise that this publication (the Moo Yei Do Bo Tong Ji) has no proven connection whatsoever to Tang Soo Do, Soo Bahk Do, Tae Kwon Do or indeed, to any of today’s Korean arts.

The Wu Yi Tu Pu Tong Tse was compiled in 1571 by Chi Chi-Kuang – the Ming Chinese General who was renowned for his successes in repulsing Japanese pirates off the Chinese coast. Later in 1621,another Chinese Mao Yuen Yi used substantial portions of General Chi’s manual to compile his own 240 Chapter Martial Arts Manual – the Wu Pei Tse (reads Bubishi in Japanese) which eventually found its way into the secret archives of Okinawan and Japanese karate schools. Obviously, the core secrets of Chuen Fa \ Fist Method (reads Kempo in Japanese) were not revealed by the Chinese authors, as these advanced techniques were only handed down orally.

Though the Chinese never taught ‘inside door’ techniques to the Koreans and Okinawans, it would be wrong to believe that the traditions which grew up in those countries were without any significant merit. Both Korea and Okinawa venerate traditions too, so these early teachings were built upon by the natives of these two countries. Like the people of Northern China, Koreans were generally quite tall and this is perhaps a partial explanation why both peoples favour leg techniques. This development of a martial art along national lines is known as “cultural patterning” and the same thing happens in any human activity – including religion.

Then in 1907, the Japanese invaded Korea and for the next thirty-eight years, practice of the Korean arts was all but eradicated and the Koreans settled to learn Japanese arts such as kendo (kumdo), judo (yudo) and karate (kong soo do – Way of the Empty Hand). Like the Chinese before them, the Japanese did not teach all the principles of their arts to the Koreans, so it was left to the latter to re-invent them. As an aside, the fiercely nationalistic Japanese did not wish to acknowledge karate’s debt to the Chinese, so they changed its name from “Way of the T’ang hand” to “Way of the Empty Hand”.Though the names (and the Chinese characters) are different, in Japanese the pronunciation remains the same – karate. Then later, the Koreans repeated this behaviour, writing off their debt to Japan and switching from kong soo do to T’ang soo do.

Then as the Korean political climate became increasingly repressive during the fifties, an attempt was made to force all Korean martial arts to come together under the umbrella name tae soo do and later, tae kwon do. Groups (such as Hwang Kee’s Moo Duk Kwan T’ang Soo Do) which refused to amalgamate were sidelined and eventually all but ceased to exist in Korea. One student of Japanese karate before the Second World War was a young Korean by the name of Hwang Kee. He learned Rembukai karate with the Japanese, Koichi Kondo and for many years after the War, Hwang Kee’s martial academy was one of those which took part in competitions with the Rembukai. This is, perhaps, not surprising since the Rembukai’s founder was a Korean, resident in Japan.

In 1945, Hwang Kee opened his own academy – the Moo Duk Kwan – and there taught what he termed T’ang Soo Do. It is obvious that, Moo Duk Kwan T’ang Soo Do is culturally patterned Japanese karate. It uses the same forms, whose historical origins can be traced to Okinawa, though it reverted to the Okinawan practice of naming the forms in the Chinese way.Thus, the Japanese Heian reverted to the Chinese Pinan, or Pyung ahn in the Korean pronunciation. As is common with Korean arts, however, Tang Soo Do has well developed kicks plus another Korean ingredient (adapted from the original Chinese)- breaking techniques. Korean kicking techniques later influenced Japanese karate, which shows how development can flow both ways.

Though Moo Duk Kwan Tang Soo Do inherits much of what it taught from Japanese karate, and the Japanese learned from the Okinawans circa CE1900 only an ‘outside door’ form of Chinese martial art, nevertheless there is one area in which it scores heavily over the traditional Chinese martial traditions and that is, in the way it teaches. The Chinese arts were only ever taught to small groups of selected people and no effort was made to teach large groups or children.

Though Moo Duk Kwan Tang Soo Do inherits much of what it taught from Japanese karate, and the Japanese learned from the Okinawans circa CE1900 only an ‘outside door’ form of

Chinese martial art, nevertheless there is one area in which it scores heavily over the traditional Chinese martial traditions and that is, in the way it teaches. The Chinese arts were only ever taught to small groups of selected people and no effort was made to teach large groups or children.

Traditional Chinese teachers rated quality much more highly than quantity and that meant that leisure martial art practice was not generally encouraged. The Japanese and the Korean arts came from a different background, with a different rationale. They sought to encourage large numbers of people to join so they were taught in a way more likely to generate and retain interest.

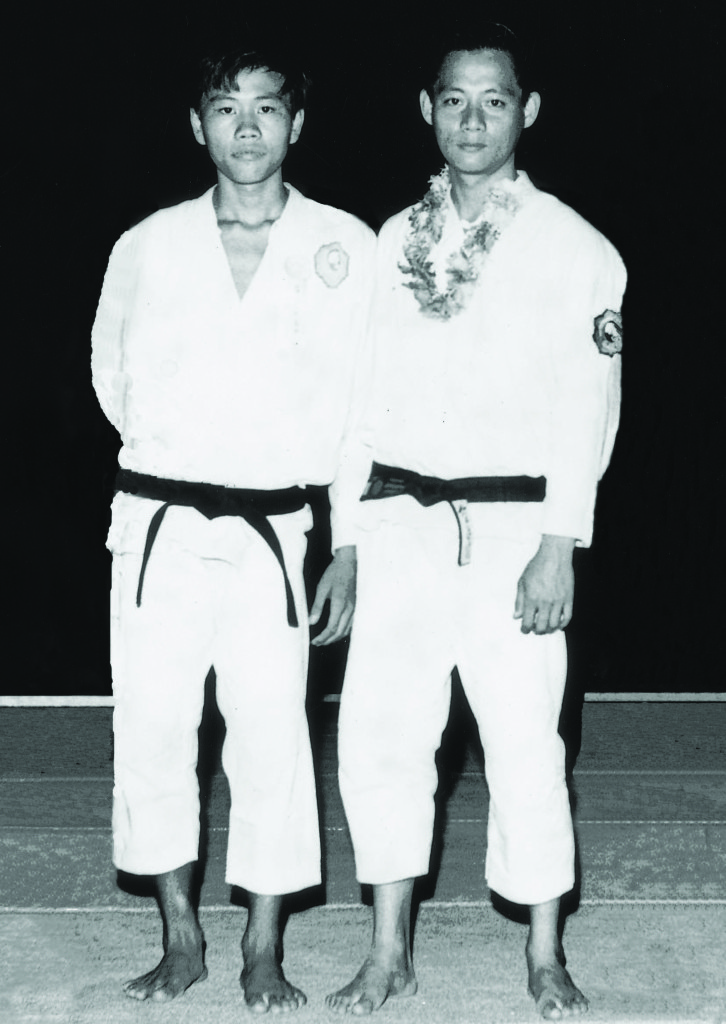

In the mid sixties I was fortunate to be the inside door disciple of Master Lim Cheng Hock (pictured with me opposite), who in addition to knowing traditional Chinese systems, also knew both karate and Thai boxing. Master Lim’s own personal style was influenced by Karate, Praying Mantis, Thai Boxing, White Crane and Shaolin Eighteen Hands Luohan. He examined each and every one of the vast array of techniques he learnt and selected those he earnestly believed would deliver the effectiveness and practicality he sought, rather than adhering to the strict traditional methods that he believed could actually stifle one’s personal progress and development. Shaolin and Praying Mantis require a conditioning process by means of which your hands and forearms are changed into weapons capable of smashing their way through the opponent’s guard. This takes several years of hard and painful conditioning to acquire. White Crane is built around the principles of footwork, using evasion to reduce an opponent’s size advantage to nothing. The exponent of White Crane always moves out of the opponent’s attack and then snaps back to take advantage of timing. Master Lim much admired Thai Boxing, with its “no-holds barred” sparring, especially the effective use of elbow and knees at close quarters.

I met Hwang Kee at a tournament in Manila in 1969 and he encouraged me to join his Moo Duk Kwan because at that time, he was actively seeking overseas affiliations. As a young athletic man, Tang Soo Do’s high kicking techniques appealed to me and the karate I’d learned before made it easy for me to switch styles. By the early seventies, my own Master had retired from mainstream martial art involvement, preferring instead to concentrate on his successful herbal/physio practice. This is common among Chinese martial artists who place great emphasis upon the healing arts.

Like its Japanese predecessor, the Korean Moo Duk Kwan’s training method was modern and used a ladder of progression (the Gup grading system) to encourage students to attain short term goals, and the dan grading system to give instructors a higher profile. It did not matter that there were gaps in the system because I was clearly teaching techniques which had an obvious application.

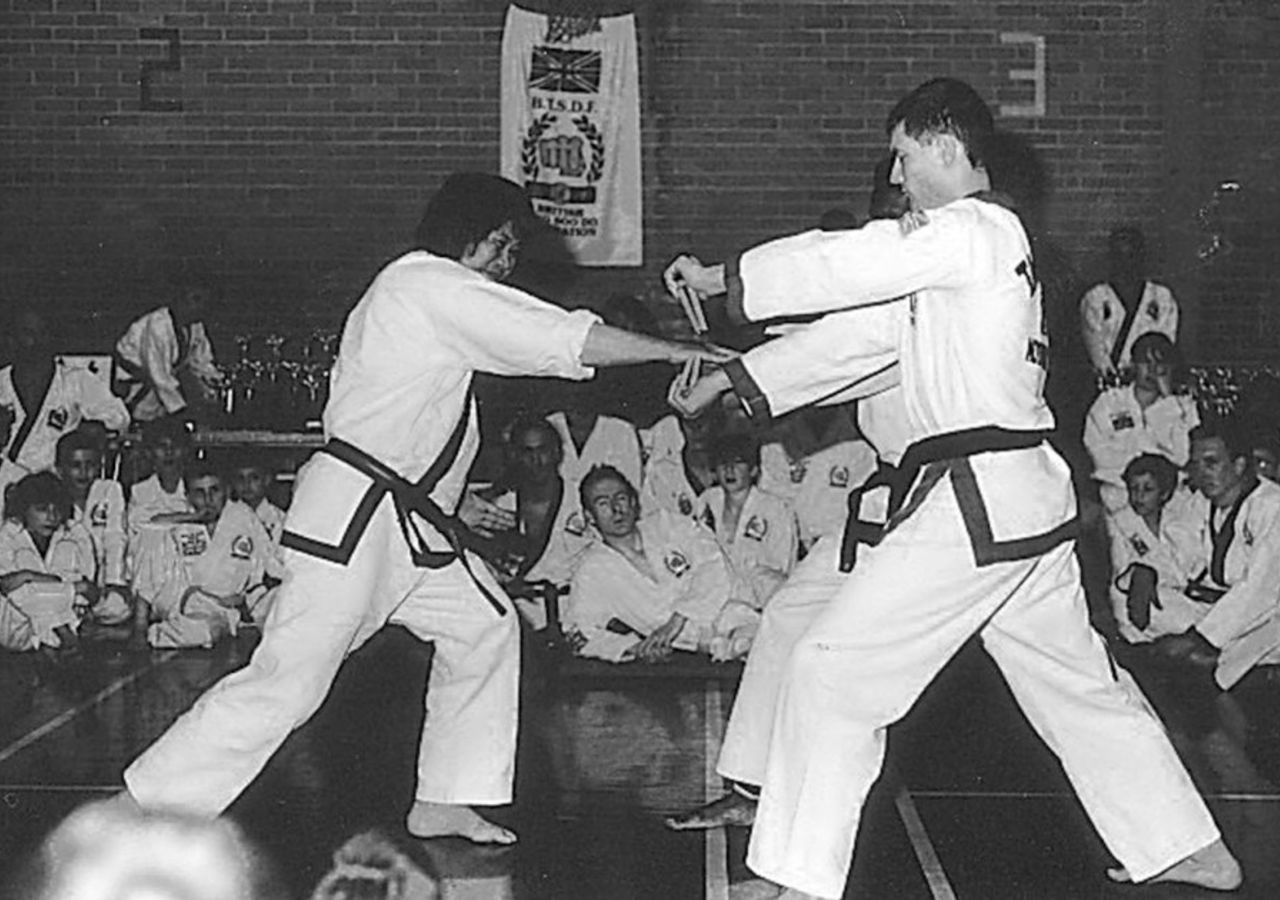

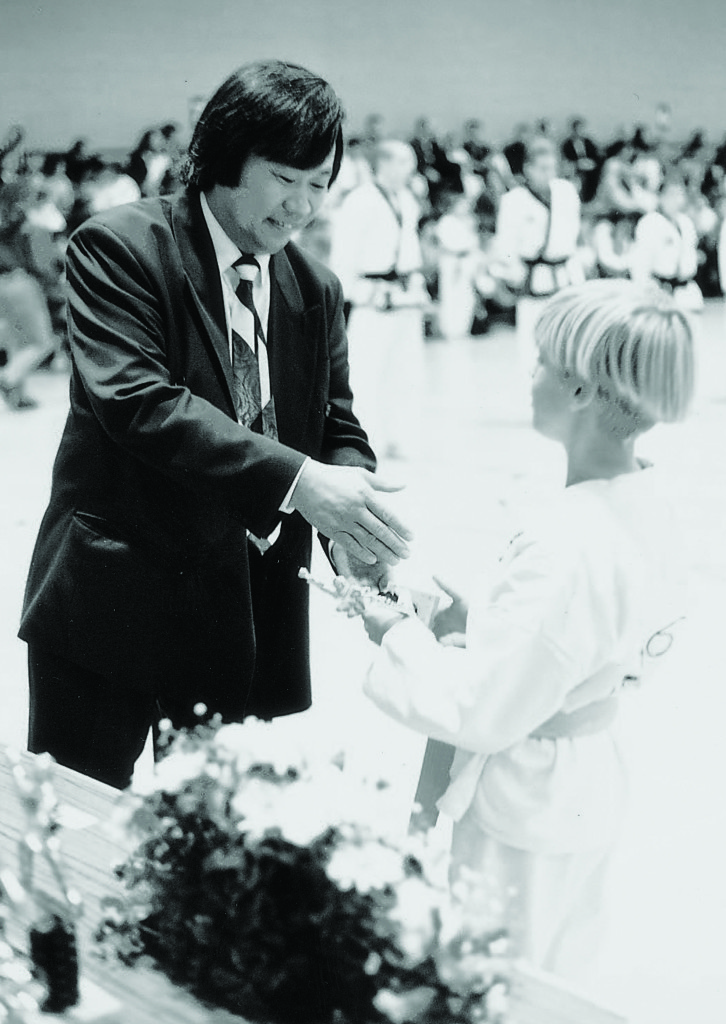

I made good progress and was soon responsible for running the largest Tang Soo Do club in the UK, plus I was instrumental in helping to find a national and international governing body. This being the case, I was prepared to persevere with the style’s apparent shortcomings.

By the mid-Eighties I was aware that the Korean Tang Soo Do syllabus simply did not provide either the challenge or the opportunities for ongoing development that I felt my students needed, which by this time included a core of 300 black belts. Once I realised this, I used the status and experience which I have learned through long years of practice to meaningfully research the Chinese systems of my youth.

The Chinese systems which my master Lim Cheng Hock was exposed to are many and various because it was in Malaysia that a great many cultures came together. Why would this be? Well, for the past 2,000 years, Malaysia, especially Peninsular Malaysia/West Malaysia, have thrived as important trading ports/stopovers because they lie along the sea route between China and India. Much of that trade passed and still passes through the Straits of Malacca. In such a multicultural environment, it is natural to find an abundance of traditional Chinese, Malay and Indian martial arts.

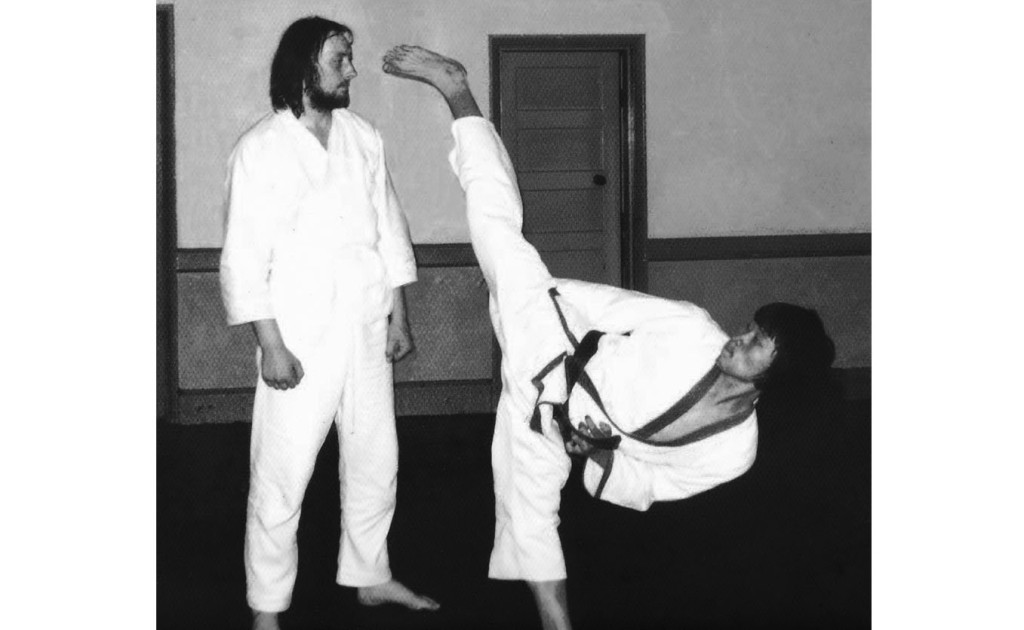

I saw clearly how it would be possible to introduce Chinese sophistication to Tang Soo Do practice whilst retaining the modern teaching methods which have been responsible for attracting large number of students. So I began to introduce a sophisticated Chinese approach, adding concurrent block/counters to consecutive actions, teaching the concepts of closed and open sides, emphasising economy and the natural flow of movement , using advanced footwork in combination with line, timing and distance, and developing short range power in addition to long range hip-generated power. Thus, I have created a complete new series of ‘Thaus’ / Patterns from Beginners to Advanced Duan levels to embrace these technical objectives. The combinations of techniques within the thaus reflects the practical usage in actual self-defence situations. Too often, traditional patterns are rigid, shrouded in mystery and ritual.

In view of this exciting and rewarding development, the naming of my new art and my school became inevitable. I referred to those Confucian ethics which are the basis of all civilised society – Ren, meaning humble and respectful, Yi being dutiful, responsible and loyal, Wu meaning ‘martial’ and Kwan meaning ‘academy’. Out of respect to those distant Tang Chinese origins, I chose to use ‘Tang Sou Dao’ which of course means ‘Way of the Tang Hand’. This development is a natural progression.

Fighting systems and martial arts have been developed by warriors. Warriors are men and since no man is perfect, then, viewed as a system of tactics and techniques, no martial/fighting art is either. A martial art may have been perfect for one individual at one time but it would be naive to suggest that it suits all people equally in all situations. It would be ludicrous to suggest that, once founded, a martial art is frozen and no further development is possible.

You see, when you think about it, a martial art is not an abstract concept floating around in a void. It takes its life and existence from and through those who practise it. It is a living tradition, a testimony to all those who have devoted their lives to its practice. As a living tradition, it must grow and develop. No martial system can afford to stagnate if it hopes to survive as a valid form of practice.

That being the case, Ren Yi Wu Kwan Tang Sou Dao was officially launched in Britain during 1998 with the full support and enthusiasm of my students. Indeed, my instructors and senior students saw the change as inevitable (especially since the Eighties) given the progression of my teaching and the increasing technical depth of practice.

The purpose in founding Ren Yi Wu Kwan Tang Sou Dao is to take the development of martial art forward into the twenty-first century. It cannot and must not become an end in itself of course, and I look forward keenly to the further progress and growth of our family tradition in the years which lie ahead. In this way, we can justly claim to be worthy practitioners of a living tradition.

The historical background and facts in the development history of Ren Yi Wu Kwan Tang Sou Dao has been taken from unbiased, well-documented and researched publications. If any reader has any material or views to further our knowledge, I would be delighted to discuss their views with them.

Grandmaster Loke